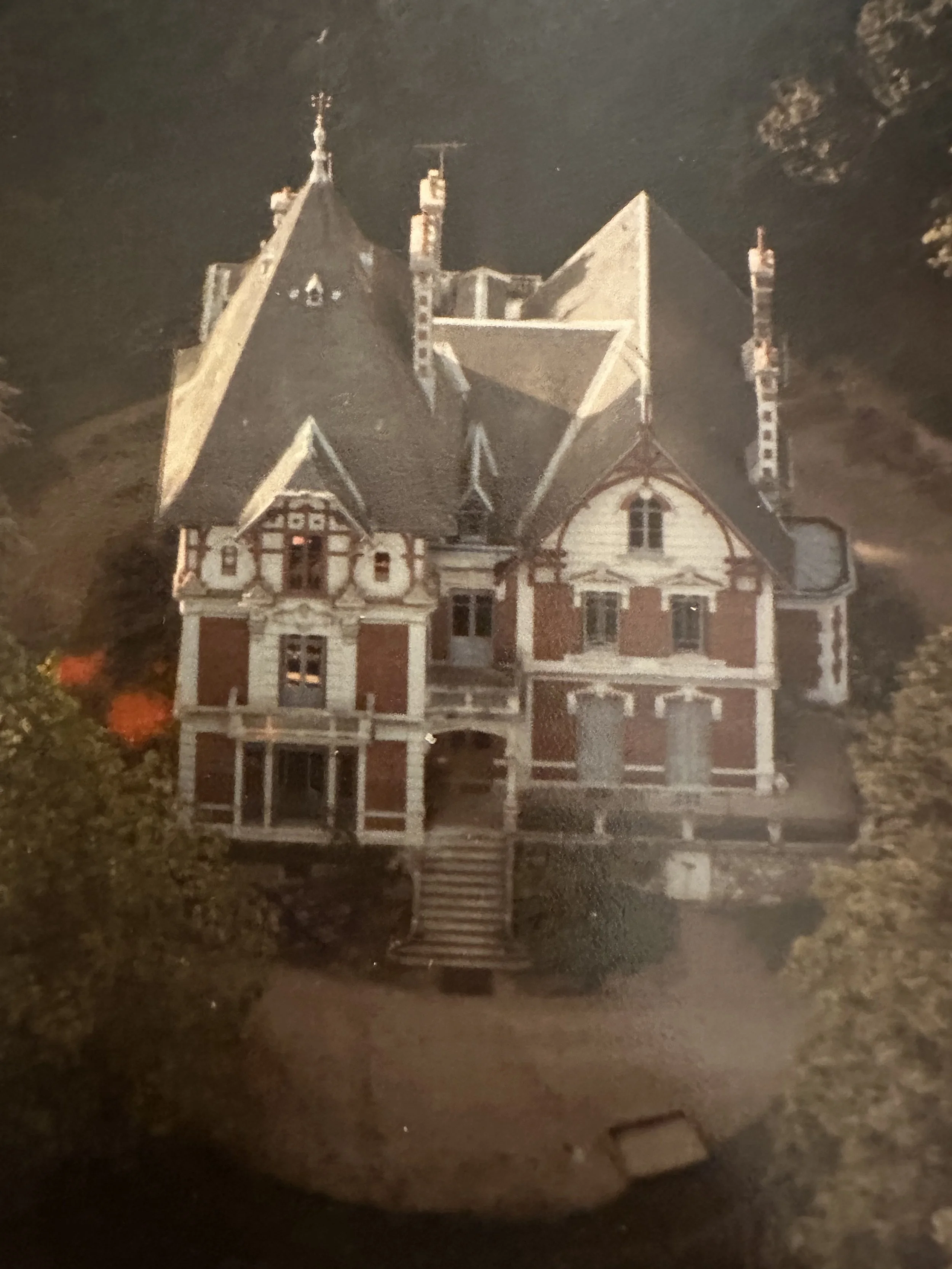

I was sent to France as an exchange student when I was fourteen. Ma famille française lived in a petit chateau, Chateau de Côtes, in Châtillon-sur-Loire, in the Loire Valley. I had a little sister named Pervenche, a little brother named Florian, mes parents, Madame and Monsieur Lamy, a dog whom I only remember Monsieur calling, ‘stupid dog,’ proud of his English, and a housekeeper who ironed my pajamas and underwear and whose face is vivid to me but whose name I’ve lost.

When I arrived in France, I spoke little French, and I ate little but Spaggettios and canned mandarin oranges. When I left, my French was only somewhat improved but my appetite was thoroughly and forever changed.

I adore French food. I love the ingredients and the names and the tools and the kitchens. I love the restaurants and the tables and the chairs and the mirrors and the tiles and the waiters and the handwriting of the specials. I love the napkins and the baskets and the cutlery and I love the allées under which one drives for a picnic.

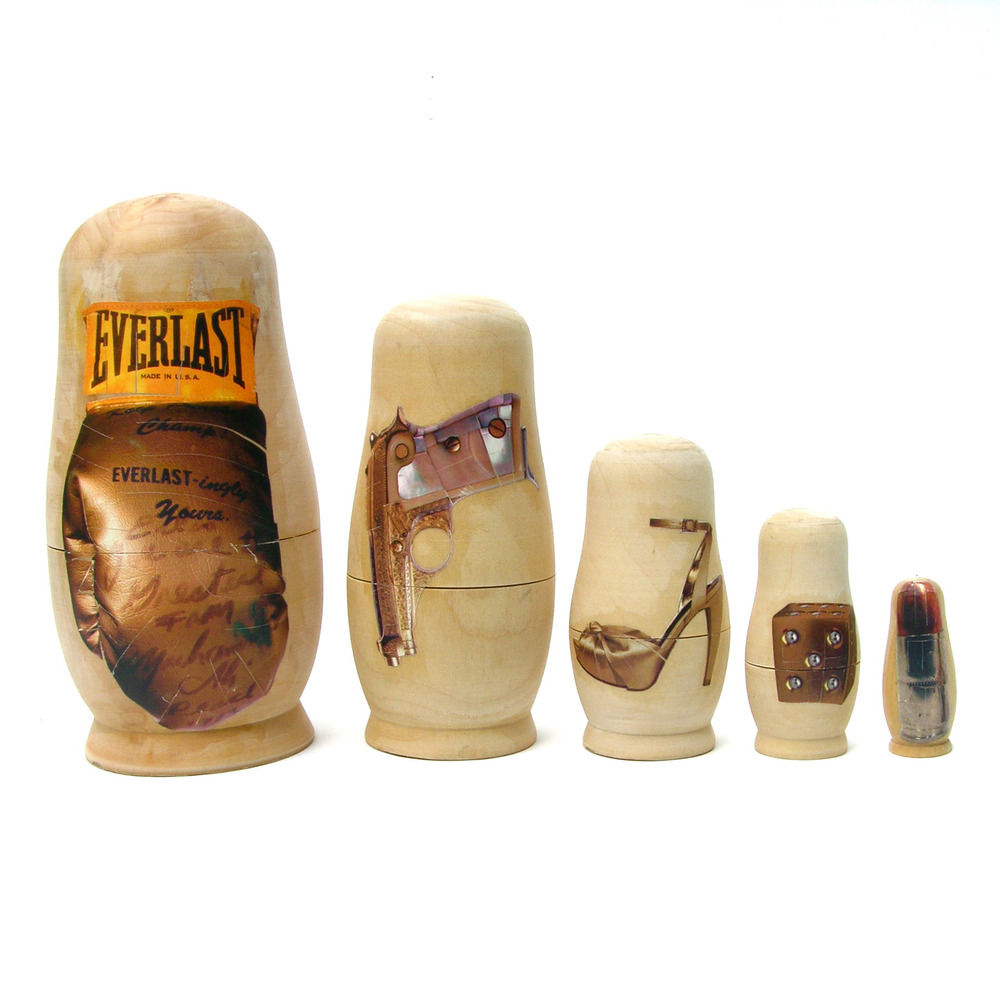

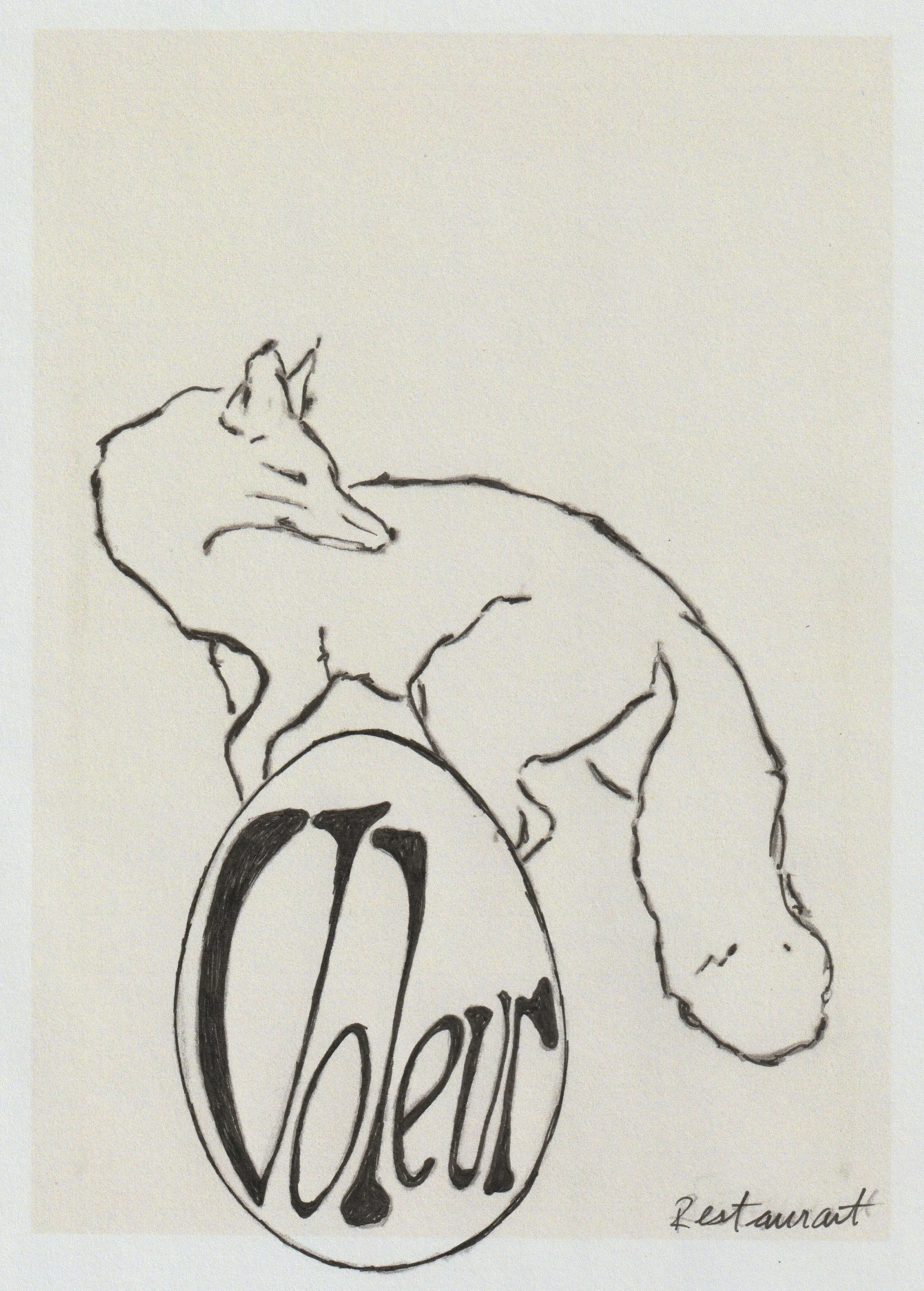

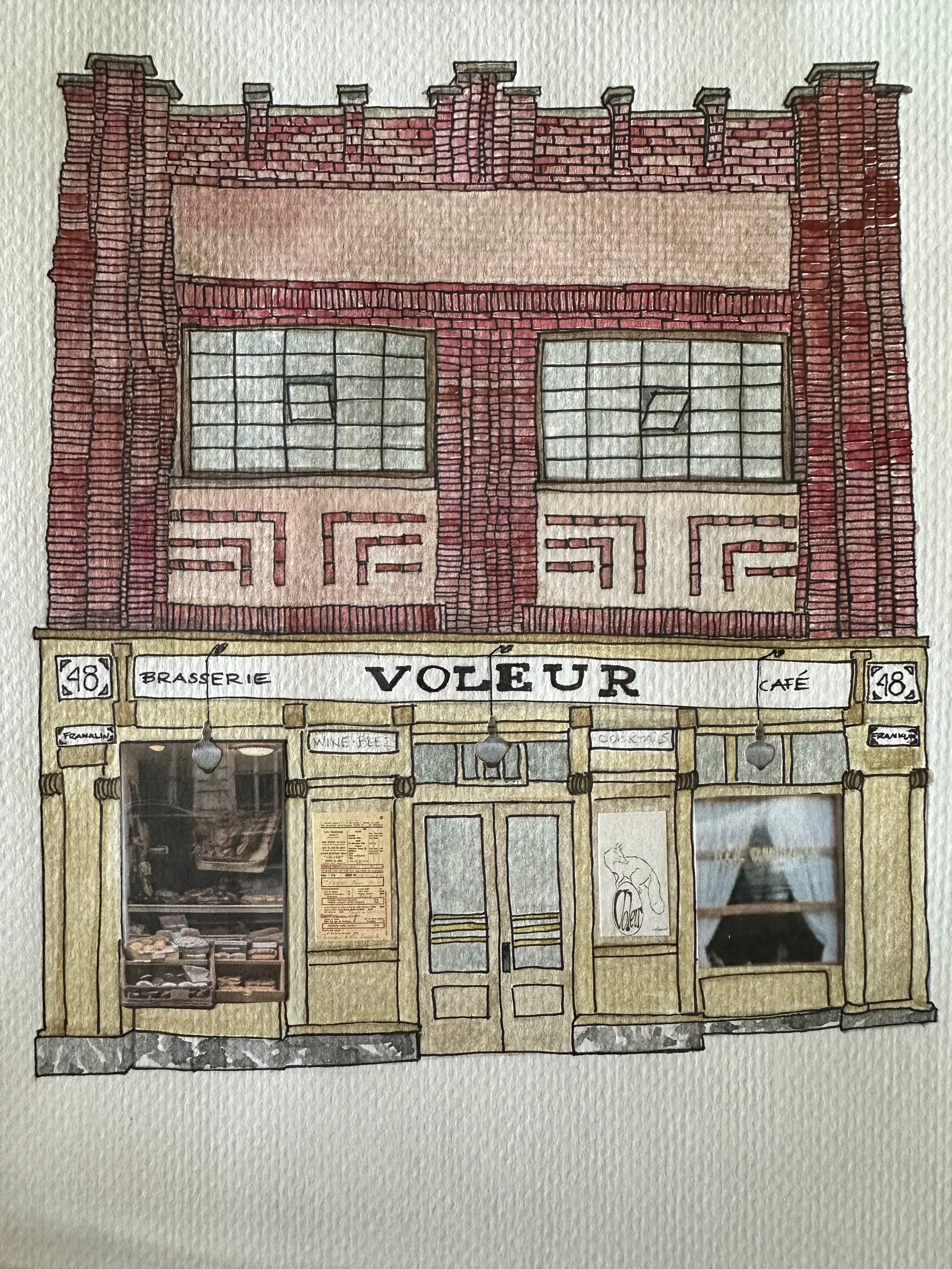

One day I will open a restaurant in 48 Franklin Street, a currently derelict building in Middletown, New York - across from the library and the skate park - and it will be called Voleur and it will be French except that Voleur means thief because it will be sort of my recipes and I am from Philadelphia. Voleur will only serve our own fresh eggs and also I am obsessed with French tarragon. On Friday nights we will serve bouillabaisse (like my second favorite NYC restaurant, Tout Va Bien does) and there will be an upright piano and sometimes I will sing in French as the eccentric proprietress who loves everything French but is from Philadelphia.

I hope that Voleur will prove a seat of the resistance. People will drink Pastis and Lillet tonics and eat buttery escargot from shells while plotting revolution. “Épater les sadiques! À bas les racistes!”

Though we had a housekeeper who provided many of our meals at Chateau de Côtes (including goûter, my favorite of which was Petit Suisse Montbourg), Madame Lamy was the chef. Though everything she cooked was worthy of her heritage, my favorite dish, the one whose nuances I can recall almost forty years later, having never had it again since, was her tarte aux abricots, or apricot tart.

Though I have tried apricot tarts every chance I’ve had over those forty years, only Gérard’s at La Bonne Auberge in New Hope, Pennsylvania, ever tasted like it was from the same family. My parents attended a black tie dinner every New Year’s Eve at La Bonne Auberge where Gérard served tarte aux abricots and always sent a big slice home with my parents just for me. Tarte aux abricots was served with lobster at my wedding rehearsal dinner but as I barely remember that I was married I don’t remember who made the tarts.

I’m thinking this must be a French country tart because every other apricot tart I’ve sampled over the years has had frangipane and sometimes almonds and that is probably Parisian.

My tart - Madame Lamy’s tart and Gérard’s tart (Voleur, or voleuse, see?) - no custard, no almonds. A pâte sablée, sugar, and apricots, c’est tout; that’s all. With a little flour to absorb the liquid. Julia Child’s recipe is similar but she makes hers with a sweet short crust, or pâte sucrée (and she half blind bakes it) and not a pâte sablée, or sandy crust, so called because when raw, when it is cru, it is gritty with sugar.

Ten years ago, Pervenche came to visit us in New York City with her son, Gabin. She had become a chef and had opened a restaurant in the south of France named Lamy Paradis. We cooked together in our tiny NYC kitchen, where she taught me to take out green shoots from the center of garlic to rid the clove of any bitterness. I told her of my decades-long quest to find an apricot tart in the same family as her mother’s. Weeks later I received a surprise package from Paris, a copy of Madame’s cookbook (she is now Madame Groussolles), “Petite Astuces et Grande Cuisine pour les Gourmands.” The inscription reads, here translated from the French, “Dear Hally, One day a very young girl journeyed to Château de Côtes and discovered ‘The Rabbit of my Father’ p.65 and ‘Apricot Tart’ p.92-94. She grew but she always loved this cake. Dear Hally, I give you this cookbook and I send you a kiss. Affectionately, Marie-Hélene”

It took me ten years to coordinate apricot season, second-language cooking vocabulary, and an afternoon free enough of other pursuits to enjoy the process, to déguster the process, in a French way.

I baked it today. I kept the apricots in an antique basket and cut them with a wood-handled knife and made the pâte with a fresh hen egg and baked it in a vintage tart tin. I don’t have an apricot tree, though I plan to. I saved the stones and cracked them open to release the kernel inside that looks and smells like an almond but is called a noyau and needs to be baked to neutralize the cyanide it contains. Once baked, I will soak 25-30 of them in bourbon for at least 3 months and then I will have noyaux extract ready for next year’s apricot season when I can make apricot-noyaux jam.

We will sell apricot-noyaux jam and noyaux extract at Voleur.

Tomorrow I will make a second tart with slightly more ripe apricots, and perhaps a third tablespoon of sugar, though I am cautious because I think what I love most about this tart is that it tastes like apricot and not like macerated fruit or fruit sugared to the point of confection. Julia Child blanches and then peels her apricots for her tart and while I can still find the fruit I may try that as well.

I will soon hit a 1000-day streak on Duolingo, where I am studying French. My score is 97, or a high B1 level of CEFR for those who celebrate. “In real life this means you can confidently handle most daily situations and explain your ideas.” Unfortunately I can’t handle any daily situations here in French. But I can grow tarragon, raise marans, and manifest a brasserie.

Happy apricot season, friends. Joyeux noyaux.